Historic Explorations is based in the coalfields of southwest Virginia. We cover a diverse amount of history, including coal mining and local history throughout the Appalachian Mountains. We also cover entertainment history, from Hollywood’s golden days to music icons.

In this compile of reflective interviews, Roy Frank Castle shares the story of a life deeply rooted in the coalfields of southwest Virginia and shaped by service, faith, and a lasting love for people and place. Growing up in the coal town of Dante, Roy talks about the values learned early in life—hard work, responsibility, and loyalty—that guided him through every chapter that followed.

Roy discusses his time serving in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, returning home to meet and marry the love of his life, Jean Fleenor Castle, and building a 67-year marriage grounded in devotion, faith, and shared purpose. He reflects on spending 45 years working as a coal miner for Clinchfield and Pittston Coal, the pride he took in his work, and the bonds formed with fellow miners underground.

The conversation explores Roy’s involvement in the 1989 Pittston Coal Strike and the broader meaning of that period for miners, families, and the labor movement. Roy speaks about the importance of union solidarity, sacrifice, and standing together for fairness and dignity—values that remained central to his life long after he retired from the mines.

A significant portion of the interview focuses on Roy’s time as mayor of Castlewood during one of the most challenging periods in the town’s history. He reflects on being elected to lead a newly incorporated town and the difficult responsibility of guiding residents through the decision to dissolve the town charter in the late 1990s. Roy discusses the financial pressures facing the community, the emotional debates among neighbors, and his belief that true leadership meant listening carefully and carrying out the will of the people—even when it meant ending his own role as mayor.

Beyond labor and public office, Roy reflects on a lifetime of community service. He discusses his decades as a deacon at Calvary Baptist Church, volunteer work with the Dante Rescue Squad, helping neighbors as the community’s trusted “furnace man,” and placing American flags throughout Castlewood as a sign of pride and remembrance. Throughout the interview, Roy returns to a simple belief: service is not about recognition, but responsibility.

This episode offers a warm and thoughtful portrait of a man who loved his family, valued his friends, and dedicated his life to the community he called home. It is a conversation about faith, work, leadership, and the quiet ways a life of service leaves a lasting legacy.

Roy Frank Castle’s life—stretching from the coal-camp rhythms of the late 1920s into the civic and labor struggles that defined the coalfields of southwest Virginia late twentieth century—was, at nearly every stage, a study in duty, persistence, and service. Born on November 7, 1927, in Dante, Virginia, Roy came of age in a world where work was not an abstraction or a slogan, but a daily requirement that shaped character. The coalfields taught him early that a person’s name mattered, that reliability was a kind of currency, and that community was not something you joined when convenient—it was the fabric of everyday life. Those lessons never left him. Even decades later, when his name appeared in connection with locally watched events, those who knew him best still recognized the same steady man: practical, hardworking, and deeply loyal to the people and places that raised him.

Roy grew up in Dante at a time when coal towns operated like close-knit ecosystems. Families leaned on one another. Churches and schools were more than institutions; they were centers of order, meaning, and mutual care. In those years, Roy learned what many coalfield men learned: do the job in front of you, do it right, staying steady, and handling responsibility—became the defining pattern of his adulthood.

That pattern followed him into military service. In 1950, at age twenty-two, Roy was drafted into the United States Army during the Korean War era. He served from 1950 to 1952, and while he did not treat that chapter as something to romanticize, it mattered deeply. Like so many men of his generation, he returned home having seen the wider world and having carried the weight of national duty. The discipline and seriousness of those years reinforced what he already believed: a person does not shrink from responsibility when it is placed on his shoulders.

Back in southwest Virginia, Roy built the life that would define him for the next seven decades—family, work, faith, and service. He married his sweetheart, Jean Fleenor, and theirs became the kind of marriage people remember as a steady anchor. Over the course of sixty-seven years together, Roy and Jean raised two daughters, Karen and Pamela. Their life was rooted in the same communities that had shaped Roy: they met in 1953, moved to Dante in 1954, and later settled for many years in Castlewood. Those were not merely addresses. They were places where family ties were interwoven with friendships, church connections, and the kind of neighborly knowledge that comes from living among the same people for a lifetime.

Roy’s working life belonged to coal. He spent more than four decades in the industry, most notably with Clinchfield Coal, later associated with Pittston—years that demanded endurance and competence in a line of work that was never easy and never fully safe. He did not simply pass through the mines; he earned responsibility. Over time, he became an equipment foreman and later a plant operator, working at the kind of industrial heart that kept coal moving from underground labor to processed output. His career spanned a period of enormous change: early wages that reflected the raw, grinding reality of mid-century coal work, and later pay that reflected not ease but the accumulation of hard-earned experience and seniority. Yet through those changes, the essence remained the same: long days, demanding conditions, and a life organized around doing difficult work well.

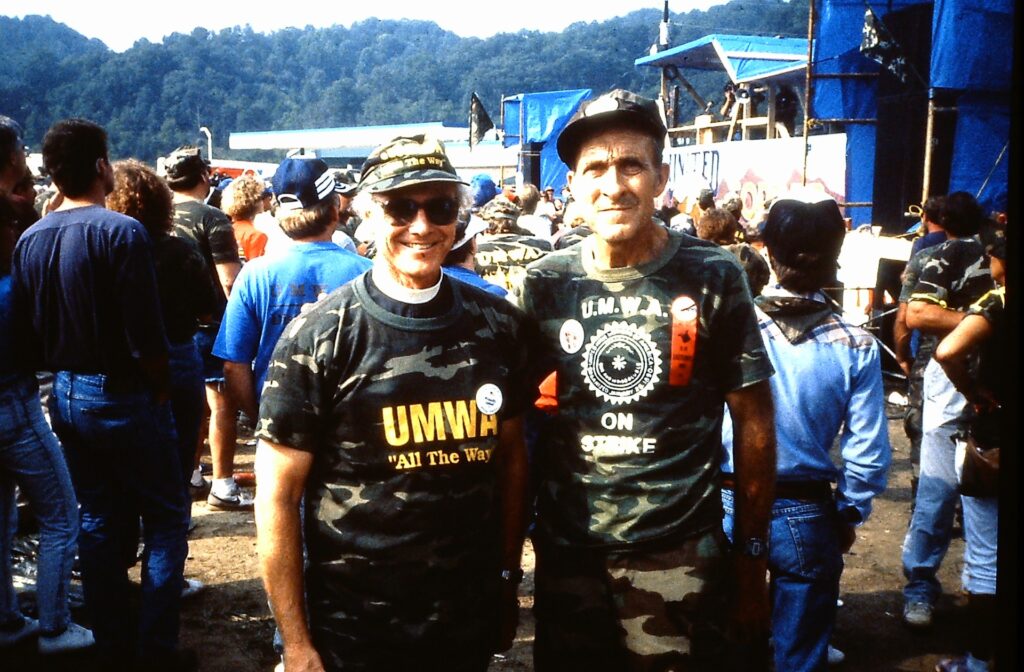

As central as coal was, union identity was equally central to Roy’s understanding of dignity and fairness in working life. He was a committed union man, associated for many years with the United Mine Workers of America and remembered as loyal to his local and his fellow miners. That loyalty took its most visible form in the Pittston coal strike of 1989–1990, one of the most consequential and public labor conflicts in modern Appalachian history.

When the strike began on April 5, 1989, Roy was sixty-one years old—an age when many people are preparing to wind down, not to step into prolonged uncertainty and confrontation. Yet he walked out alongside fellow miners, joining a struggle that would last ten and a half months and test families and communities in every direction: financially, emotionally, and socially. The strike became known not only for bargaining and negotiations, but for the intensity of its protest tactics, the visibility of mass arrests, and the sense among many miners that their future and their dignity were on the line.

Roy’s role in that chapter was not as a distant figure but as part of the human backbone of the strike—the experienced men whose willingness to endure made the union’s position credible. He was present during some of the most tense moments, including protests tied to the Moss No. 3 preparation plant. He wore a camouflage cap with a button that read “Proudly Arrested,” a small detail that captures the spirit he carried: determined, unashamed, and grounded in the belief that collective action sometimes required personal risk. He understood the potential for violence and escalation, but he also understood what it meant to stand firm. When the strike ended and victory was celebrated, he described it as one of the greatest things to happen to labor—language that reveals how he saw the conflict not as a short-term fight, but as part of a larger moral and historical story about workers’ rights.

And yet Roy’s choices after the strike were marked by the same practicality and generosity that shaped everything else. After returning to work, he was reassigned to a late-night shift that would have pushed his hours deeper into the early morning. Rather than accept that change, he chose retirement. He did not frame it as bitterness. He framed it as a matter of timing and responsibility: he had earned the right to retire, and he believed younger men needed the opportunity. In that decision, people saw what they had long known about him—he could be firm, but he could also step aside when it served others.

Work and labor, however, were only part of Roy Castle’s service. Faith was another pillar that ran through his entire life. He was a founding member of Calvary Baptist Church in Castlewood and served as a deacon for more than sixty years. That kind of tenure is not a title; it is a lifelong pattern of care—showing up, supporting people through hardship, helping to guide the congregation, and living his faith as practice rather than performance. In many communities, the church is where people see each other at their most vulnerable: illness, grief, financial struggle, and family crisis. Roy’s presence there, year after year, became part of the quiet strength that holds a community together.

His service extended into emergency work and everyday assistance as well. He volunteered for many years with the Dante Rescue Squad and served as its treasurer—a role that requires trust, attention to detail, and the confidence of others. But perhaps the most widely felt, day-to-day form of his generosity was the work that earned him a particular reputation: Roy was “the furnace man.” For more than sixty-five years, he repaired and maintained heating and cooling systems, boilers, and the mechanical essentials that keep homes livable—especially in winter, when a failed furnace can turn from inconvenience to danger. People knew to call Roy because he could fix what others could not, and because he treated people fairly. He did not treat that work as a business opportunity to exploit. He treated it as part of being useful, part of helping neighbors stay safe and warm.

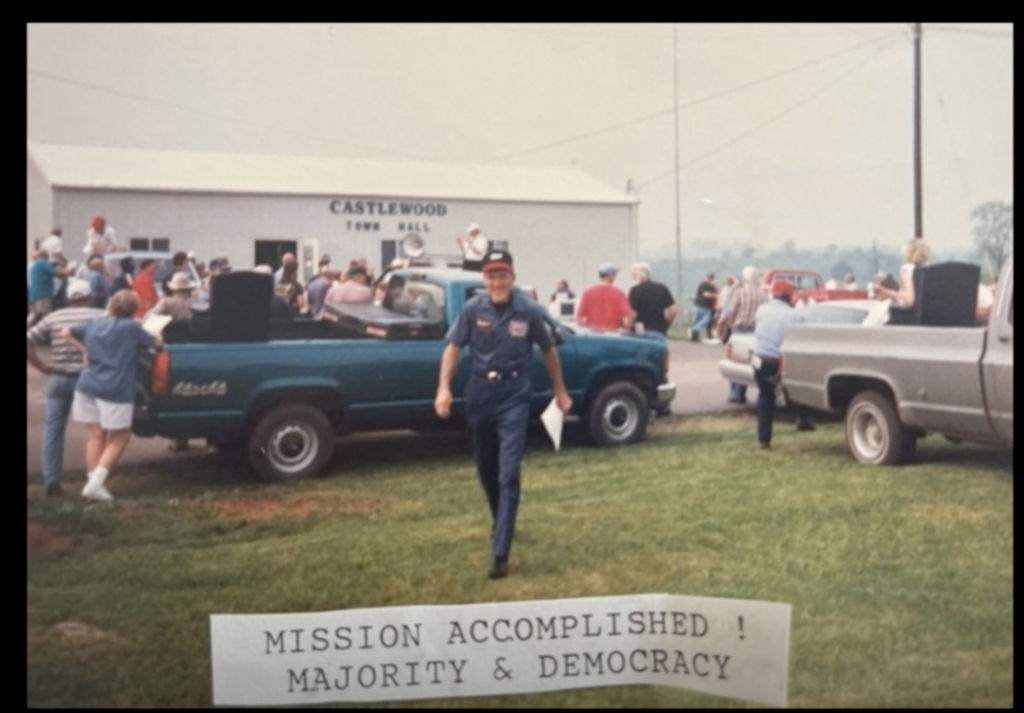

Roy’s life also included a rare and historically notable civic chapter: his service as mayor of Castlewood during the movement to dissolve the town’s charter. Castlewood incorporated as a town in 1991 with hopes of building infrastructure and attracting economic development. Over time, however, many residents grew dissatisfied—particularly with property taxes and the sense that services were being duplicated between town and county government. Roy became a leading figure in the push to undo incorporation, arguing that residents were effectively paying twice for overlapping government functions.

In the November 1997 election, he won the mayor’s race with overwhelming support, aligned with a slate committed to repealing the town charter. Once in office, he moved swiftly, reflecting the same pragmatic approach that marked his working life. The town’s police department was ended, returning those duties to the county and reducing municipal expense. Roy framed the situation bluntly, emphasizing that people were tired of unnecessary taxation and bureaucracy, and that the town structure, in his view, should never have been created.

The referendum to dissolve Castlewood’s charter was close and hard fought, with organized opposition campaigning to keep the town incorporated. But the majority vote went the way Roy and his supporters sought, and Castlewood entered the complicated process of winding down municipal operations. That process required selling town property and closing out services—unpleasant work, often misunderstood by those outside the immediate context. To Roy, it was not a matter of emotion; it was a matter of responsibility. Dissolution required liquidation and closure, and he carried out the voters’ decision with a straightforwardness that did not bend to sentiment.

Ultimately, the charter repeal was formalized at the state level, and Castlewood returned to unincorporated status within Russell County. The broader significance of that chapter is that such municipal reversals are rare. Roy’s mayoralty therefore became associated with an unusual moment in Virginia local governance: a town forming, then later choosing to unmake itself. Whether people agreed with his position or not, even critics often acknowledged the same traits: Roy was direct, practical, and committed to carrying out what he believed the community had decided.

In later years, Roy continued to live as he always had—rooted in family, faith, and service. He took part in preserving local history through an oral history interview for the Dante History Project, placing his voice and memory into the record of the community that shaped him. He remained, in the words of those who remembered him, approachable and human—someone who could carry serious responsibilities while still being “up for a little mischief and a Pepsi.” That detail matters because it reveals what formal titles cannot: he was not merely respected; he was liked. He was the kind of man people trusted, but also the kind of man people felt comfortable around.

His loyalty to labor never faded with age. Even decades after the Pittston strike, Roy remained deeply aware of what union protections had meant for miners—healthcare, pensions, and dignity in retirement. In his nineties, he traveled to support striking miners at Warrior Met Coal in Alabama, a remarkable late-life act that reflected not novelty but continuity. He believed in standing with working people, and he believed that the rights he enjoyed in retirement were the result of sacrifices made by earlier miners and sustained by ongoing solidarity.

Roy died on January 1, 2026, at age ninety-eight, at home in Castlewood, surrounded by family. He was preceded in death by his wife Jean and his daughter Karen, and survived by his daughter Pamela (Pam) Evans, along with grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and a wide circle of friends, fellow church members, and fellow miners who regarded him as a steady presence.

To summarize Roy Castle is to describe a life built from many roles that reinforce one another: a Korean War-era Army veteran; a coal miner whose career extended across more than forty years; a union man who stood through one of the most significant labor struggles of his time; a church deacon for more than six decades; a rescue squad volunteer and trusted treasurer; a skilled tradesman who kept neighbors warm and safe for more than sixty-five years; and a mayor whose tenure became tied to a rare municipal dissolution. But to those who knew him, the through-line was simpler and more personal. Roy Castle lived in the old coalfield way that measures a person by steadiness: whether he keeps his word, whether he helps when needed, whether he works hard without complaint, and whether he remains loyal to family, faith, and community until the end.